December 31, 2009

Victims of the Image: Ignobility for the Noble Savage

Native Americans have endured a long legacy of distorted images. They’ve been slurred, mocked, and exploited through graphic and verbal stereotypes in mass art, literature, film, and culture. For decades they’ve been portrayed in reprehensible caricatures, toxic misrepresentations, and false romantic ones. Although some of these manipulated images have not always been explicitly bigoted, most have been devastatingly untrue and have evolved into humiliating character portrayals at the hands of visual artists and designers.

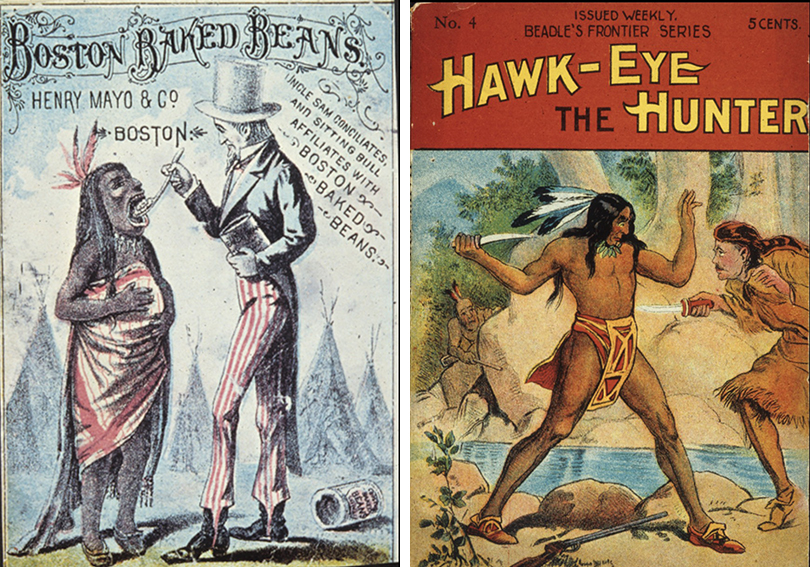

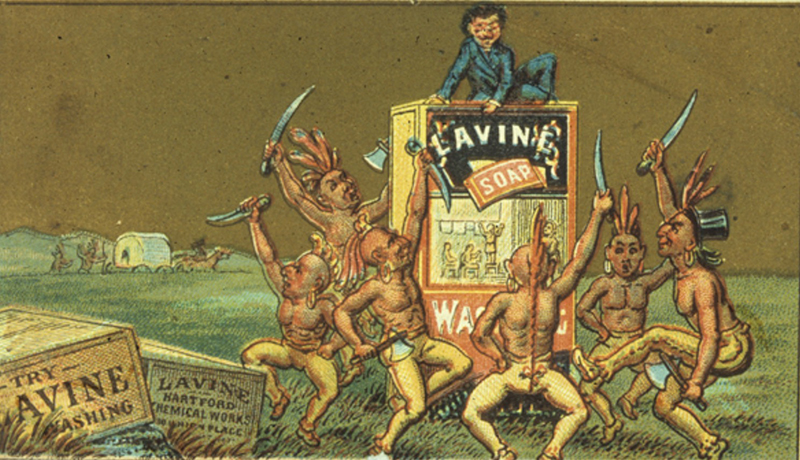

America’s indigenous peoples were branded with two fundamental personas: Noble savages or heathen primitives. Both imbued with the sense that because they were aboriginal they were unchristian and uncivilized. In imagery—and likewise as people—they were treated as foreigners on their own lands and suffered generally poor treatment, forced migration, confiscation of property, and mandatory re-education in U.S. government schools, all justified as an outcropping of American manifest destiny. Even the few instances where Native peoples gained a modicum of status through oil wealth, they were portrayed as clownish poseurs in white man’s trappings. More often they were heathen or servile in the scores of pulp and penny dreadful tales commonly circulated during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They were portrayed in cheap literature and comic strips as a race of menacing renegades flaunting white man’s law, which enabled the old world conquerors to murder, subjugate, or otherwise forcibly “civilize” the new world’s indigenous population. None other than the celebrated English author of “A Christmas Carol,” Charles Dickens wrote in an 1853 article that noble savages should be “civilized off the face of the earth.”

Most school children were made aware that Christopher Columbus, in mistaking the Caribbean island on which he planted his flag was the subcontinent of India and thus calling its inhabitants Indians, was the progenitor of early stereotypes. The term “Indian” stuck, even though there were hundreds of indigenous tribes that comprised this imprecise designation. Although some artists and later photographers attempted to portray Native peoples in realistic and romantic contexts, bastardization and hybridization of such depictions quickly occurred, lumping diverse peoples into the same demographic bucket. In a nation as obsessed with skin color and caste as the United States the term Red Man or Redskin (and variations thereof) became a common pejorative to describe Native peoples—even if it was not always meant in demeaning ways.

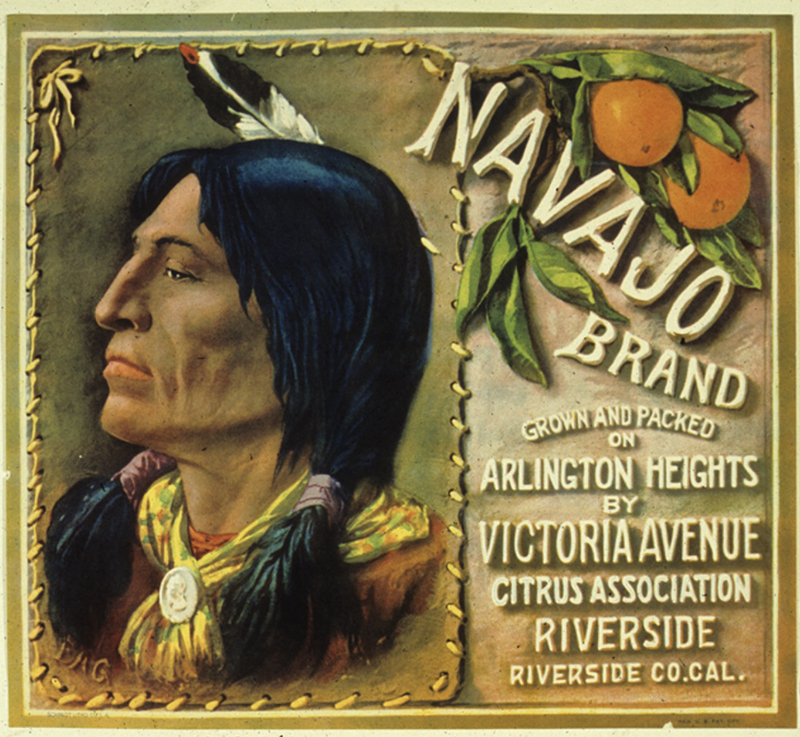

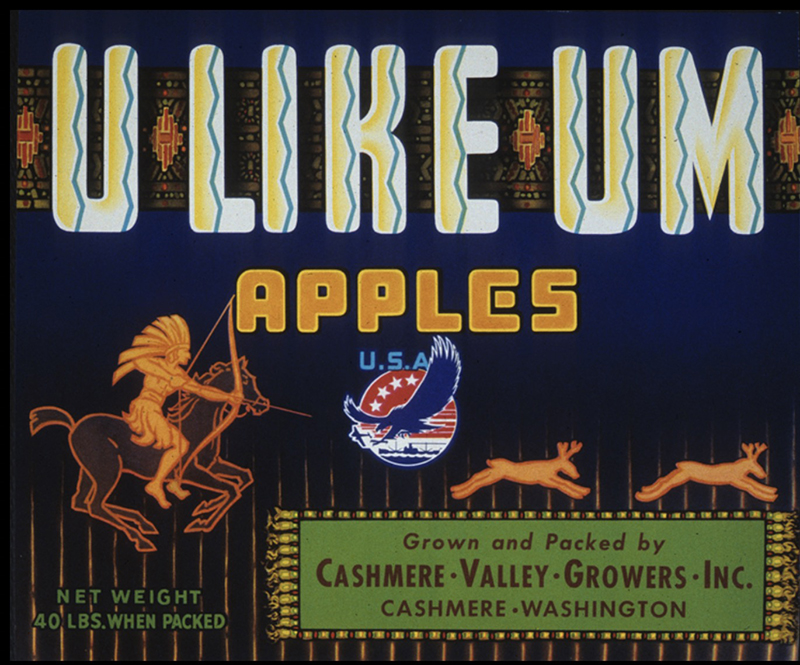

Benign cartoons and demonic pictures of scalping, marauding, and war painted injuns validated the sanctioned apartheid of Indians onto reservations or “off the face of the earth”. A systematic process of homogenizing different tribes with unique customs, language, dress, and rituals, turning them into the noble and heathen stereotypes, effectively reduced them from proud people to marketable curiosities. The inevitable fiction that they were not civilized enough to be Americans was exacerbated and perpetuated in the popular consciousness through waves of propaganda—from book and magazine illustration to advertising to logos, trademarks, and product packages. Knowing little—and being taught less—about the history of Native peoples fostered greater ignorance and allowed the purveyors of popular American culture to design deceptions that persisted for much of the nation’s early and not too distant history.

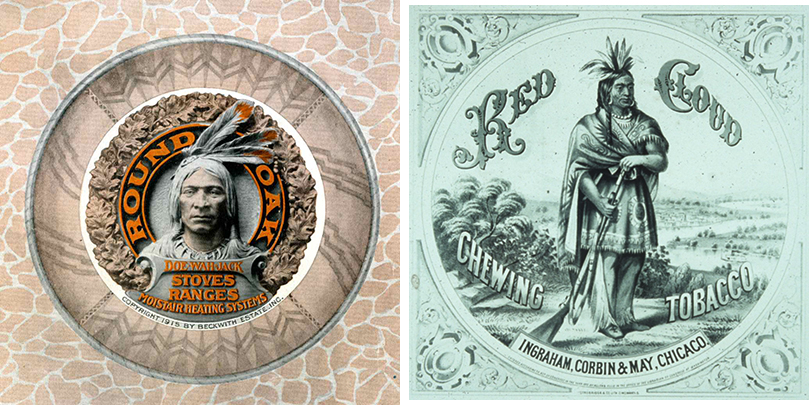

The cigar store Indian was one of the earliest advertising and marketing exploitations of the Native American, equivalent to the Uncle Tom in African American culture and the rapacious Jew in immigrant culture. In fact, it dates in the Americas from the late 1700s and only began to decline and largely vanish in the twentieth century as restrictions on public spaces limited their use on sidewalks. Transforming the Native into a comical character holding cigars was an effective means to tame the idea of the heathen into submission through ridicule. As spokespeople for certain brands and product genres, the relationship between Native Americans and tobacco certainly fostered a widespread stereotype—and although it was not as pejorative as some nastier depictions, it lacked any semblance of respect.

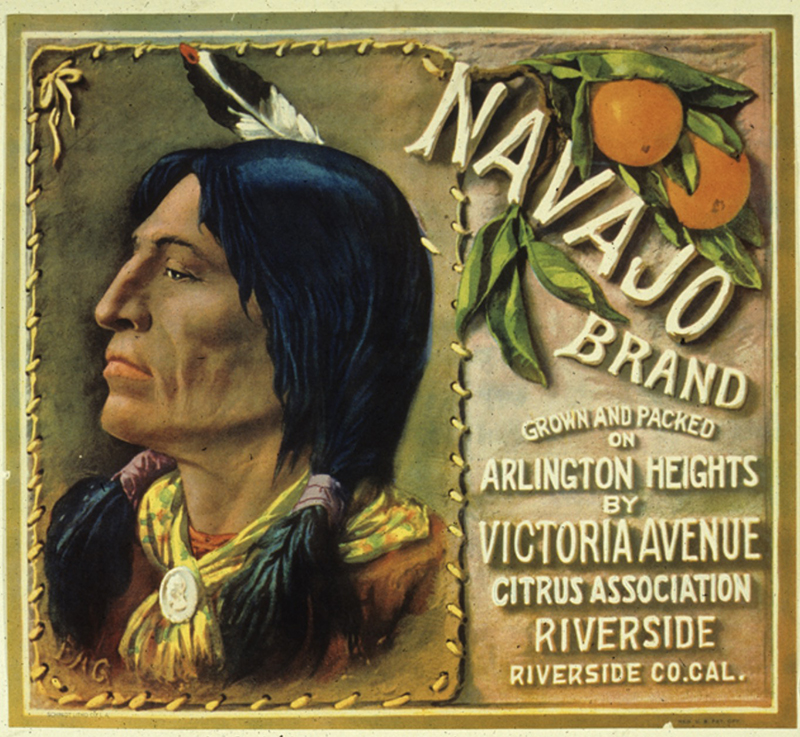

Perhaps slightly more product-appropriate Native American identification was linked to a wide range of crops, hunting and gathering, and other behavior—but nonetheless lead to stereotypically silly trade characters for packaged goods and premiums. Often these signs and symbols devolved into cartoon representations with a set of ridiculous facial features. Exaggerated tales of fictionalized Indian exploits, customs, and lore further piqued interest in and raised the levels of Native Americans as objects of curiosity on the one hand and derision on the other.

By the end of the 19th century, images of Native Americans had become so commonplace in American advertising that it was taken for granted, and criticism was minimal if at all. Almost all of these trade card, advertising, sheet music, and other popular images had nothing to do with the real lives that Native Americans lived, nor as commerce impinged on their lives, the products and services to them. Rather, most uses of Native Americans were gratuitous and, according to many critics, harmful from the point of view of the people represented. A 2014 Time magazine, noting that the Washington Redskins lost their trademark, stated there were still “over 600 active trademarks for insignia that feature Native American men and women, registered to 450 companies.” (See here for an interactive graphic.)

Why so many? Despite the racist underpinnings, Native Americans did represent a great swath of the American imagination and culture. Tribes have been proudly used as names for towns, sports teams, consumer products, and more. The Noble Savage embodied the nobility of the innocent—the natural being—and in many instances piqued the white man’s interest precisely because of their exotic clothing, crafts, and more. This fed into advertising’s exploitative need to find allure in almost anything, especially directed at a mass American market by usurping one or another (supposed) characteristic of American Indian culture. Looking back at the images from the early twentieth century, even honest representations appear stereotypical: Indians in “native” attire, such as beads, feathered headdresses, and fringed buckskins. Quite often the connection of the imagery to the product and its attributes was vague or absent but associating brands with Indians somehow had cache. Businesses integrated the Native American ethos not just into posters and ads but also into their brand names and trade mascots. Like other branding devices, such icons as the Land O’ Lakes Indian Maiden named Mia holding the butter box, painted in 1928 by illustrator Arthur C. Hanson, which has been streamlined over the years, still represents the butter. Likewise, Argo corn syrup’s anthropomorphized Indian maiden continues its staying power.

There are also scores, if not hundreds, of company brand names with tribal or other Native American-derived names. Shawmut Bank, Mohawk Paper, Crazy Horse Malt Liquor, and more. A 1994 article in Cultural Survival “What’s In A Name? Can Native Americans Control Outsiders’ Use Of Their Tribal Names?” notes that “Indigenous beliefs, names, symbols, and practices clearly are worth money in the American marketplace,” even if the products are non-indigenous. Although not all words or images can be protected by law, it says that federal and state systems of trademark registration can stop companies from using their names on products, such as the Jeep Cherokee. “A trademark is a name, a brand name, a group of words or symbols that companies use to identify their products and services.”

The use and misuse of Native images in the popular culture, although possibly done with more sensitivity, has not ended in commercial endeavors. The idea of the “Indian” continues to have allure in the profit sector.

Perhaps the paradigm shift occurred over four decades ago, when the Ad Council partnered with Keep America Beautiful to create a powerful visual image that dramatized how litter and other forms of pollution were hurting the environment, and how every individual has the responsibility to help protect it. The ad featured a striking Native American actor with a tear running down his cheek named Iron Eyes Cody. Known as “The Crying Indian,” the commercial first aired on Earth Day in 1971. Created by ad agency Marstellar, Inc., the campaign used the line, “People Start Pollution. People can stop it.” The ad became one of the most memorable and successful campaigns in advertising history and was named one of the top 100 advertising campaigns of the twentieth century by Ad Age magazine.

Native Americans were more blatantly associated with various produce and products other than tobacco in the recent past than they are today. Their collective images have morphed or disappeared over the past sixty or seventy years. Indians have been replaced by other stereotyped characters, but there are still products, industries, and teams that have yet to let the old ways go.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Related Posts

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Gratitude? HARD PASS

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Recent Posts

‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison ‘The American public needs us now more than ever’: Government designers steel for regime change Gratitude? HARD PASSL’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own pathRelated Posts

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Gratitude? HARD PASS

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,