September 27, 2017

I Loved to Draw

The following is an excerpt from Chris Ware: Monograph, out now from Rizzoli and published here with permission from the publisher. — The Editors

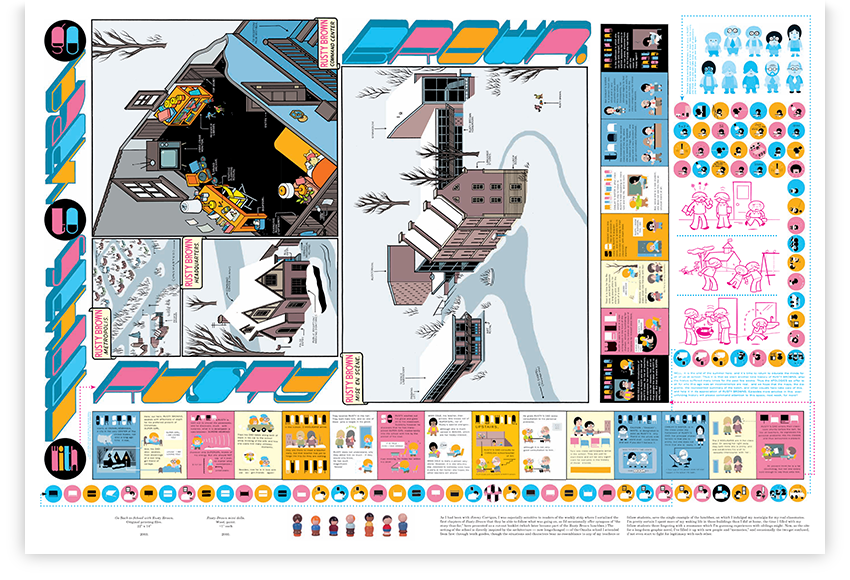

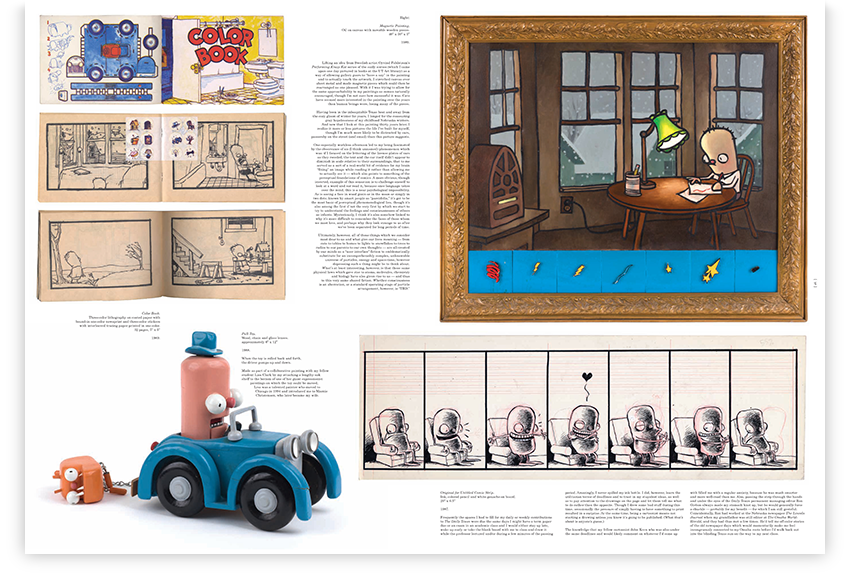

As a kid, I loved to draw. Though such a thing seems strange to say now, since “love” certainly doesn’t describe how I feel when I sit down to work as an adult. Something I think maybe I liked the alone part more than the drawing part, the relative security of sitting by myself in my room or behind my open school desk or in my grandmother’s basement feeling safer than walking the hallways of my school where at any moment I could be called names or jumped on by upperclassmen. Poofy-haired, unathletic and prone to making irritating animal noises in my pre-adolescence, I spent a lot of time by myself as a kid. This self-fulfilling loop of relative isolation fostered an ability to make something appear at the bottom of a paper pit that then could take me somewhere else, sometimes even beyond my own solitude.

© Monograph by Chris Ware, Rizzoli New York, 2017.

Serious comics fiction is uncommon, the comics language at the moment more likely to find its taste of reality and complex human anguish in memoir form (Art Spiegelman’s Maus being the aboriginal, still-defining example) as we cartoonists slowly grow up with the medium itself. As a young artist, the easiest way to acquaint oneself with communicating real, felt emotion is to try to communicate the emotions one has, well, already felt. But at the same time, our memories are faulty, uncertain and fragmentary; regardless of whether we consider ourselves memoirists or storytellers, we are all always recomposing our lives from ever-decomposing pieces and stems. In short, we are all natural-born fiction writers. And I believe it’s that very ability to tell stories which makes us most human. There’s very little difference between me sitting at a table drawing stories and a normal civilian trying to remember how he or she wasted the day or his or her childhood. The processes of visualization, of reconstruction and, most importantly, of paying attention to what “feels right” are exactly the same; I just happen to write it all down. Ultimately, we’re all working on our own graphic novel of our lives, and in doing so trying to understand, feel through and hopefully empathize with others as well as with our selves. Whether one’s own story is more or less true is frequently less important than how it sits in our memories. And besides, that story is all we have.

© Monograph by Chris Ware, Rizzoli New York, 2017.

© Monograph by Chris Ware, Rizzoli New York, 2017.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Chris Ware

Related Posts

AI Observer

John Maeda|Books

Should we teach AI to reflect human values, emotions, and intentions?

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Related Posts

AI Observer

John Maeda|Books

Should we teach AI to reflect human values, emotions, and intentions?

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books