Jessica Helfand|The Self-Reliance Project

April 28, 2020

Tracing

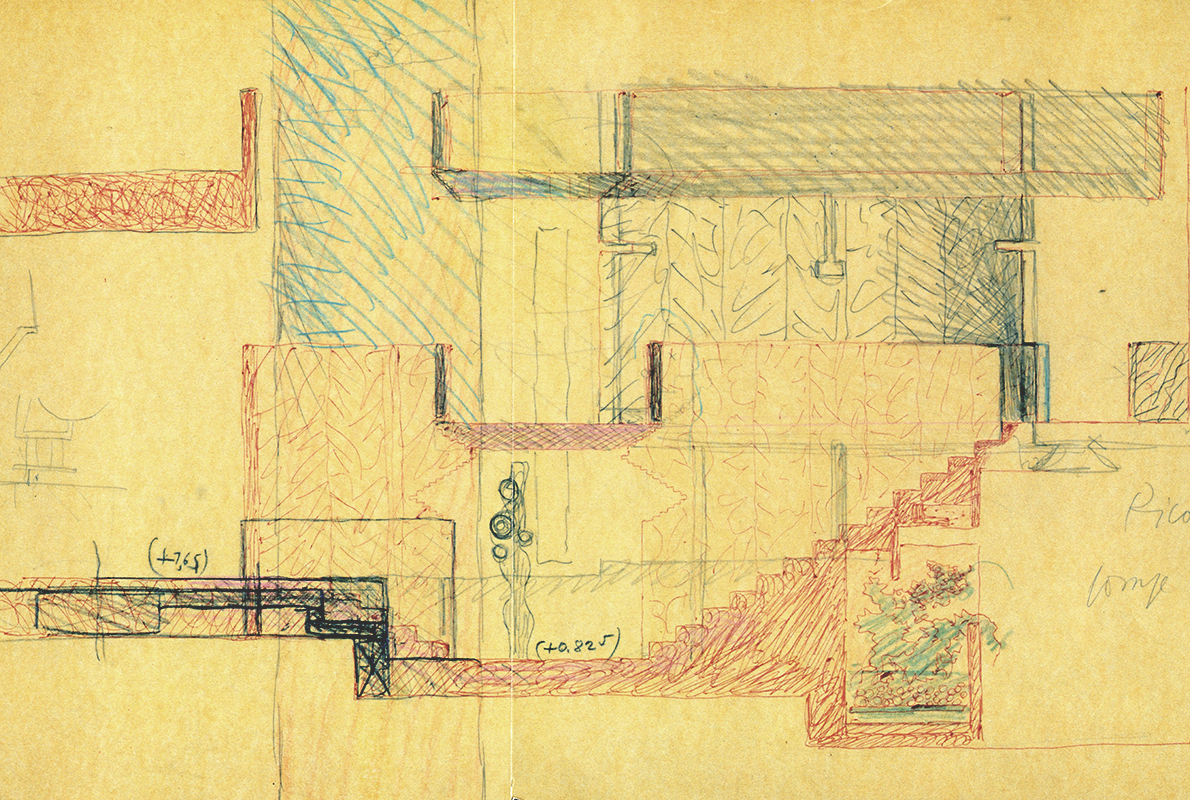

Carlo Scarpa, Drawing on yellow trace (detail). About 1981.

Last night I had a nightmare in which my front door had been open all night. I felt a surge of vulnerability, only to have fear turn swiftly to wonder when I realized (still dreaming) that the hinges had mysteriously been inverted, so that the door opened in the wrong direction.

Night-dreams trace on memory’s wall shadows of the thoughts of day, wrote Emerson.

John Updike once observed that Emerson liked to write about people in their stressed psychic anatomies. (Indeed.) What might he have made of this moment, all of us at home by mandate and masked by law, adding new words like “contactless” to our vocabularies, and dreaming of inverted doors?

Tracing, it turns out, is more than an involuntary narrative delivered by a relaxed mind: it’s a process and a practice, a verb as well as a noun, and a flexible, foundational material that functions, in the studio, as a kind of connective tissue. Tracing allows for a new idea to be layered upon another, or sketched over in such a way that new and old can be viewed together: the magic here is that drawing on a diaphanous surface provides the opportunity to both refine and deviate from visual thinking in real time. It’s a membrane that exposes the underbelly of an idea—a way to think in stages—and seeing those stages pulls you along in your thinking. (The root of trace is the same as the root of tractor.)

For those of you keeping score, trace is the opposite of post-it notes, those small squares of adhesive-backed opaque paper that have, regrettably, become our go-to visual shorthand for modern creative engagement. Post-its are building blocks, popular collaborative tools for constructing things, typically on walls, and often in groups. (Tough love: anyone can be creative on a two-inch square of paper.) Trace, on the other hand, is a revelatory material, a conceptual hinge shepherding you from what was, to what is, to what could be. Both are additive, but only one lets you see what came before. In the act of tracing, the past is in view, the process is revealed, and the journey is powerfully exposed.

This all bears examination right now as we enter a new era of something called contact tracing, an epidemic-driven public health initiative that will demand identifying, interviewing, and if necessary, isolating people with whom an infected person might have had contact. This introduces a definition of tracing far from the studio realm, except that it points out how resistant we are not only to the past, but to sharing it. We are not, as a people, culturally predisposed to looking behind us: progress, after all, is a forward march. To embrace it is to self-identify as a futurist, viewing history with deep resistance, as James Joyce’s literary alter ego, Stephen Dedalus, once did: a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.

But the truth, as we well know, is that those yesterdays are as much a part of you as your tomorrows will be. Contact tracing should begin not with others, but with seeing yourself, and your work, through the phased gradations of time’s passage. Tracing what was against the constellation of your own layered life means embracing all of it with honesty, equanimity, and discernment. Progress, in this context, means looking backward to look ahead. It may not be easy. There will be always be nightmares. But there will also, unquestionably, be joy.

The Self-Reliance Project is a daily essay about what it means to be a maker during a pandemic. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox here.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jessica Helfand

Recent Posts

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green: ‘Wicked’ spells for struggle and solidarity Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.