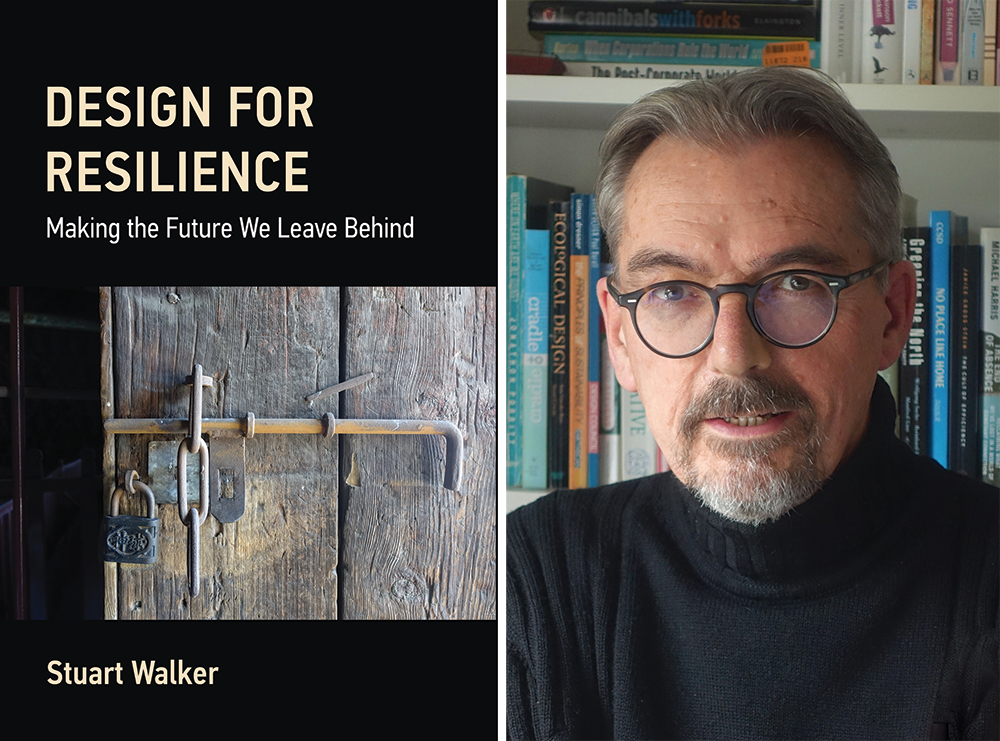

Editor's Note: The following excerpt is from Stuart Walker's new book Design for Resilience out now from MIT Press. The text and images are reproduced here with permission of the author and publisher.

Criticism in the context of art and design is concerned with analysis and evaluation of creative works and judicious discernment of their contribution. It is an interpretive process that may involve reference to theoretical perspectives and historical precedents, and it strives to understand and contextualize the content, themes, merits, and deficiencies of a work or works. A critique is the resulting piece of writing, usually in the form of an article or essay, that articulates that criticism.

Unfortunately, the discipline of design does not have a well-established culture of criticism. The term design critique is more often used to refer to the oral or written reviews that take place during studio courses in design schools. When people do write about design, as Glenn Adamson, head of graduate studies at the Victoria & Albert Museum, has observed, it is usually, “so deeply entrenched within the design field, so closely tied to its professional goals, that the writing’s ultimate effect would always be promotional rather than critical.” This contrasts with art criticism, which does have a lineage and conventions, even though it has become much diminished in recent times. In the early twentieth century, art criticism was more prominent, and its critics were inclined to think on a larger scale, comparing works by different artists as well as the views of other critics. In this way, their discussions and judgments were contextualized within broader comparisons, rather than being confined to the particular exhibition or work at hand, which is often the case today, especially among critics whose work appears in the popular press.

Design criticism is seldom taught in universities. There are some postgraduate degree schemes that use the term, but these are relatively rare and, even here, most of the teaching revolves around history, theory, and research methods. While design criticism involves these topics, it also requires consideration of different positions and perspectives and the development of critical judgments. It aims to understand, interpret, contextualize, and critique a work of design in terms of its significance to the time in which it was created, to the history and development of the discipline, and to broader societal concerns. It might include reference to aesthetics, design theory, design history, other works in the same genre, or the relationship of this particular work to other designs by the same person. It can also include considerations such as the originality and innovation of the product or process, the quality of production, and the relationship of these to broader issues, such as ethical, environmental, and economic factors. The view that design needs to develop a more broadly informed approach to design criticism is shared by others. Katherine Moline points out that while research has been growing in design history and contemporary practice, design criticism lacks weight and is usually limited to pragmatic and functional concerns, especially as they relate to the market. The discipline of design needs substantive, broader-based design criticism because active critical engagement and reflection are essential if the discipline is to move forward in ways that are informed, thoughtful, and relevant to the times. The writer, design historian, and curator Stephen Bayley is probably the best-known design critic in the United Kingdom, and he does contextualize and evaluate design within a wider vista.

In this present discussion, I will consider examples of recently created material culture and, in the process, demonstrate the need for design to become more reflective, self-critical, and discerning—both in professional practice and in academia. However, by design criticism, I am not meaning high-flown discussion that is so specialized and esoteric that it is neither accessible nor appealing to practitioners or a wider audience. Design affects everyone, so design critique is not something that should be confined to the rarefied atmosphere of the university.

Wenheyou Market, Changsha, China

Bogus Bohemia

A colleague in Changsha, in south-central China, invited me to give a talk at the university’s design-research symposium. I was pleased to accept as I was already conducting research in other parts of China, and this was a good opportunity to learn more and meet new people with similar interests.

I arrived the day before the conference and was given a tour of the campus, which has a number of ancient buildings and a history dating back to 976 CE, and I learned something of the culture of this strikingly beautiful region. The final evening was given over to the conference dinner, and we had been promised a special treat. The venue was a place called Wenheyou Laochangsha Lobster Restaurant, or simply Wenheyou Market, the name at the entrance to the complex.

To all intents and purposes, Wenheyou Market is a large, highly stylized food court attached to a shopping mall. It occupies several floors, and in addition to restaurants and smaller food outlets, there are various retail stalls, a crayfish pond, barbershop, lottery-ticket seller, billiard hall, and bookstore. The mall is newly built but seems old because it has a decrepit style that mimics a working-class urban district of 1970s China. It has “designed-in” tumbledown walls, broken cables, defunct air-conditioning units, poor housing, and hole-in-the-wall shops, all rendered in a carefully choreographed, dirtylooking, and well-worn aesthetic—a kind of large-scale shabby chic. There is even a period cable car regularly circuiting the top floor.

During dinner, everyone was enthusiastically extolling the place. I seemed to be the only one in our party who was feeling perplexed and uncomfortable. None of it sat well with me because none of it was real— all was illusion and facade driven primarily by commercial intent. The whole concoction abuts and is part of a conventionally designed shopping mall, selling all the usual brands in all the usual layouts. Just this part had been done up in what can only be described as an “urban-poverty theme park.”

Yet despite its contrived aesthetic, its questionable moral qualities, and the fact that the whole thing is a pastiche, it recently won an international design prize—a “Best of the Best” Red Dot design award. The award statement says the mall aims “to allow the elderly to recall every detail of their childhood, while young people can experience and partake in the old lifestyle. . . . As a successful alternative to familiar and globally identical shopping malls, visitors can here experience the recreation of an authentic atmosphere—an experience that also invites them to connect emotionally to the past.” I was amazed at the design team’s meticulous attention to minutiae in their attempts to recreate the past, in the architecture itself as well as the interior design of the restaurants and shops. It had all been accomplished with considerable expertise, a remarkable eye for detail, and impressive technical skill. And the mall is undoubtedly successful—it has proved to be especially popular among young middle-class urbanites and tourists. However, contrary to the award statement, it is anything but authentic.

During the flight home, I thought more about my experience at Wenheyou Market. The reason it troubled me was not just that the architecture was a conceit—a piece of nostalgic flimflam—it was also the fact that it had received an international design award and was being liberally praised by senior design academics. What did this say about the state of contemporary design? Whatever the answer, I felt it was probably not very complimentary!

The award statement claimed that visitors can “experience the recreation of an authentic atmosphere.” This piece of designer doublespeak bears little scrutiny. Something can be either authentic or a re-creation, but it cannot be both. Moreover, while it may be a re-creation, it is more precisely a recreation of whatever was in the designer’s head. It is certainly not a re-creation of the past. Rather, it is a selective, idealized notion of the past—one that is supported by a host of modern conveniences, technologies, expectations, and standards. It is all surface and fakery, creating an emotional experience with none of the true implications, responsibilities, or deficiencies. There is no depth to engage with, no requirement for commitment and no real feelings. It is a simulacrum—having merely the appearance of the real thing but possessing neither its substance nor its authentic qualities.

It aims to conjure a time not so long ago that, supposedly, was filled with warm, deep communal relationships, and everyone led peaceful, harmonious lives. A time when one’s daily needs could be satisfied by street vendors selling vegetables, eggs, fruit, and snacks, and one could get a haircut from an itinerant barber. A time when children could play safely among the narrow, winding streets, or hutongs. The Wenheyou complex is created against this background, and it skillfully paints a vivid picture. However, the fact that it is so visually convincing makes it all the more disconcerting; it misleads through plausibility. But unlike true art, the attention to detail and accuracy of the reproduction actually closes down the imagination rather than opening it up. Consequently, the mall’s aesthetic is entirely specious, and it is this quality of deception and insincerity that makes it so morally questionable.

This kind of design can be understood as kitsch, that category of creative production, whether art or design, characterized as pretentious and of little value. Wenheyou Market falls into this category because it aims to touch its visitors by invoking superficial emotions, which are consciously elicited through aesthetic evocation.

Its nostalgic references are designed to promote a sentimental longing for a time now passed. It is kitsch because of this attempt “to have your emotions on the cheap ... the easy avenue to a dignity destroyed by the very ease of reaching it.” It conjures a world of never-ending childhood, a world of fantasy aimed at adults, and, consequently, it represents an infantilization of adulthood. Through such means, adults in contemporary society suppress and constrain themselves by transforming reality’s more unsettling and disturbing questions into pacifying, puerile answers.

With their relatively recent rise in wealth, many people in China seem to be proving just as susceptible to the beguiling indulgences of kitsch as any Hollywood tycoon or European aristocrat. In China’s development of commerce and tourism, there are new “ancient” castles built in traditional styles imported from different regions. The resulting mélange is blandly representative of some idealized notion of a past that never was. In Beijing, just south of Tiananmen Square, the creation of Qianmen Street involved displacing thousands of citizens and demolishing a centuries-old neighborhood. The area has been turned into an upscale shopping and tourist destination—all in a kind of 1930s style architecture that looks, feels, and is entirely phony.

Wenheyou Market may be the latest trendy place for young metropolitans, and it may be less obviously kitsch than Disney’s Main Street, U.S.A., or Thomas Kinkade’s cutesy cottages, but it is kitsch just the same—a bogus Bohemia bolted onto a shopping mall. As its restaurant menu confirms, it is pretending to be a China of a different time, when grandmother still made wholesome, home-cooked dishes and the family sat around the kitchen table together watching old shows on a fuzzy black-and-white TV.

Theodor Adorno suggests that when architects become tired of conventional functional forms and try instead to give free rein to their fantasies, their work inevitably falls into kitsch: “Art is not more able than theory to concretize utopia, not even negatively.” Umberto Eco reinforces this by pointing out that history always defies imitation—history has to be made. Eco was discussing the artificial edifices created by the wealthy in Florida and Southern California, but his words apply equally to many of the nouveau riche projects found in today’s China. Wenheyou Market, in particular, seems to suggest a longing for a simpler, less-wealthy time and some nostalgic remorse for what has been swept aside during China’s recent economic boom.

Note: To read more from Design for Resilience you can order it on Amazon, or directly from MIT Press.