April 30, 2018

Design for Democracy: Building Community Power

AIGA’s seminal initiative, Design for Democracy, recently launched Building Community Power. It’s a program in partnership with Nonprofit VOTE that 1., pairs a selection of about 10 AIGA chapters with nonprofits in their local communities, and 2., invites designers from across the U.S. to create visually impactful, intelligent, and accessible social media graphics that target first-time voters, youth, and new immigrants and to empower activists on the ground.

Intrigued? You can get involved. Submit your social media content by 11:59 p.m. PST April 30 for a chance to be featured on the NASDAQ screen in New York City’s Times Square this coming May.

This dialogue between Rich Hollant, co-chair (with Frances Yllana) of AIGA Design for Democracy committee and Brian Miller, executive director at Nonprofit VOTE, compares practices and perspectives: how a social impact designer with deep experience in community organizing and an advocacy expert in nonprofit voter engagement both approach the challenge of building community power. This interview serves as an overview of our project hope and vision in 2018: to connect people to what is rightfully theirs.— Laetitia Wolff

“In the United States, a crucial part of any community is the citizens’ fundamental right to vote. Sometimes misunderstood and underestimated, this right is essential, and at its best, inspiring through the evidence of its own impact. To truly achieve this impact, we must go out and get every citizen registered and eager to make their voice heard.” —Rich Hollant

Laetitia Wolff: Rich, what makes this project particularly exciting to you? How is it a means of talking about community engagement rather than just civic engagement?

Rich Hollant: In my experience, civic engagement doesn’t occur without community activation. At the root of AIGA’s Design for Good platform is the effectiveness of designers to connect with communities and help them recognize their own power. Aligning cultural power and community power is something that design is adept at delivering. What’s exciting about Building Community Power is that we can dig into one of the empirical pieces of democratic power—the vote. We need to understand community structure and motivation better so as to better align with community, get folks out to vote, and to use their collective power to alter the governing system. I think it’s a great opportunity for us across the country to learn from each other in diverse neighborhoods, cities, and towns, and to develop a set of best practices for how we connect authentically in community.

A submission to Building Community Power 2018 by MGMT Design. “Some things just have to happen in a certain order. In the same way that you should chew before you swallow, this is a reminder that in order to VOTE you must first REGISTER.”

LW: What do you hope the partnership with Nonprofit VOTE will bring to the project?

RH: The hubris that design can fix everything in communities oversteps our place. But the idea that we can work in collaboration with groups that are connected to communities and can guide us deeper into our own neighborhoods—so we can understand them better and can work together to build systems that empower people in the way that they want to be empowered—that is really getting at the promise of what design can do here. That’s why I’m excited about this partnership. It underscores the community mantra, “Nothing for us without us.”

A submission to Building Community Power 2018 by MGMT Design.

LW: Brian, from your perspective, what drives successful civic engagement?

Brian Miller: I would agree with Rich for the most part, including the fact that it really starts with community engagement. One of the things that excites me about this partnership is that through design and the various creative approaches AIGA chapters will bring, we can tap into deeper cultural levels of the work that we’re doing; aligning cultural power to community power. That’s a big part of why people vote. People vote because of values they hold, because they feel like they’re a part of the community. I think that if we’re going to successfully engage folks and bring them into the process—especially those who’ve been sitting out or pushed to the sidelines because of apathy or perceived lack of, or real lack of influence in the process—we need to tap into the cultural dimension if we’re going to succeed in closing those gaps.

RH: Brian, you touched on this notion of cultural disenfranchisement—the inaction that works against people’s best interest. You could be disenfranchised from the vote through any number of external forces. Those conditions have existed across generations and concern entire segments of our population. Many of these folks seem to have distanced themselves from the essential value of the vote—the big value isn’t in the promise of a specific short-term outcome from participation, it’s in participating in a democratic process that has the potential to recast the system that has impact over their lives. The promise is in the faith in the process, not in the outcome. This is hard to maintain when the process itself has either been elusive or unfair to many of us. So, I’m curious what your successes have been in getting folks to reclaim their rightful power.

BM: I understand the power reference, but I want to skip to a slightly different point, which is about culture and the role it plays in voting and shaping policies. Policies absolutely are a key factor, and reinforce gaps in voter participation.

Recently I attended this workshop held by a group of artists talking about economic inequality. And the speaker asked participants “How many of you got into this work because someone showed you a compelling fact sheet?” And of course, no hands went up. People who get into that type of advocacy work usually go back to a visceral, compelling story of some inequity they’ve experienced or witnessed, some deeper life story that got them into fighting inequality. It was never because of a bunch of facts and figures put in front of them. If we’re going to move more people into action, we need to tap into the stories. There are of course policies that contribute to gaps in turn out. People don’t turn out because there’s nothing compelling on the ballot that moves them to vote. If it’s not a competitive election, or the two parties are so close that they just don’t see the difference it will make.

Identity, website for Mash-up Americans. “We created a new brand identity and website for the Mash-Up Americans to give voice to those of us who identity as multi-ethnic, multireligious, multi-anything (i.e. actual Americans).” Image courtesy Nikki Chung and Dungjai Pungauthaikan, Principals at Once-Future Office, who was just selected by AIGANY to collaborate with Community Votes, as part of the Building Community Power project.

LW: So, Brian, what makes those stories stick to get the vote out?

BM: There’s a segment of America, and I’m going to use a race analysis here; “white America,” for whom there’s a perception that it is civic duty. You look back at history and the founding fathers involved in creating this country and feel some sense of ownership. White America has some of the highest voter turnout in the country, but not far behind are Black Americans.

African-American voter turnout has matched white voter turnout in many recent elections. In the most recent election, it was behind white voter turnout, but only by five or six points. The large-scale civil rights struggle, wherein people fought, bled, and died for the right to vote, created a shared cultural heritage within the African-American community. I’m sure there are parents and grandparents who are lecturing their kids, “You better get out there and vote.” That’s a part of the cultural stories that are told to encourage voting.

A lot of it is also the history organizing that’s been happening within the African-American community. But, within the Asian Pacific Islander (API) and Latino communities, voter turnout still lags almost 20 points behind. It’s a huge gap because within the Latino and API communities there is no equivalent of the civil rights struggle story that people felt connected to. Nevertheless, there are cultural stories we can tap into. Art and design can help tap into our shared culture. I don’t know if it’s the answer, but it can be part of the solution.

LW: What other issues affect voter turnout rates?

RH: Culture is definitely important. Meeting people where they assign meaning can be a powerful canvas for organizing. Likewise, power is important to keep in mind as well—organizing around culture harnesses power that can be leveraged for equitable representation. I’ve noticed a tendency to underplay power for softer ideas like culture. I really want to get back to the idea that power, backing a desire for change, is what sets communities toward their desired outcomes. This project will help us observe potential alignments across communities so we are considering scale even as we engage locally.

With an increased representation of leadership in the black community running for both national, state-wide, and community-wide office, folks are starting to see themselves in their representatives. This has a tremendous impact in encouraging participation in the civic process. There are studies that document the impact of majority-minority districts on voter turnout. Voters show up where there’s a high likelihood that their voice and vote won’t be marginalized. That, to me, is one of the benefits of organizing around culture. Culture allows for collective power instead of distributive power—which is more equitable, stronger, and has intrinsic momentum.

I’m interested in how the efforts that we’re making together will address the issue of individual or family isolation in the context of aligning embedded cultural values to address “why” to vote. Through my organizing training and the community engagement work I’ve been a part of, addressing this isolation has become de rigueur. When folks aren’t naturally coming together around urban centers, we’re not organizing broadly. We have to work through one-on-one relationships which exhaust resources very quickly.

Identity, mailer. Historic Districts Council. “In anticipation of recent local elections, we worked with the Historic Districts Council (HDC) on a campaign to inform New Yorkers about the importance of historic preservation and how it is affected by their local elected officials.” Image courtesy Nikki Chung and Dungjai Pungauthaikan, Principals at Once-Future Office, who was just selected by AIGANY to collaborate with Community Votes, as part of the Building Community Power project.

LW: Have you developed any useful strategies for dealing with that isolation?

BM: A lot of the work we do contributes to breaking down the isolation. Part of the reason Nonprofit VOTE works through existing nonprofit service agencies like human service agencies, food pantries, health centers, etc., is to indicate we aren’t engaging anonymous people. This is the place where I drop off my kid for afterschool programs. This is the person who gives me my flu shot once a year at the Health Center. The work we do is designed specifically to leverage trusted relationships with messengers—actors who have a long history in the community. We don’t do parachuting. We work through existing institutions in the community that have trusted relationships and that have cultural competency. In that sense, yes, it gets beyond the isolation. There’s a lot of data out there about different strategies for voter engagement. Some people think you could just do a lot of online voter engagement work, and you can, but you’re going to get the low-hanging fruit: the folks who just need a little reminder; mostly white, educated people. That doesn’t scratch the surface of closing the gaps.

RH: That approach is structured to widen the gap—it’s inequitable.

BM: Yes, and direct mail has a very similar limited reach. If you really want to engage communities that have been marginalized, you need to look people in the eye and tell them their opinion matters, their voice matters, and help them walk through the process of becoming engaged citizens.

RH: Working with agents is key–and I don’t mean just nonprofit agencies. I mean emerging leaders; folks from the community trained to foster engagement. In nine months of a Get Out the Vote campaign, you can’t both disseminate information and build a trust that’s going to lead to substantive change. The way that we do that is we tap into the outlets that are doing this 12 months a year, and have been for the past decade or more, out of neighborhood action groups and churches; people who have deep ties to their community and can throw their arms around it substantively. The objective then becomes more focused: it becomes about making the investments to align voter empowerment into existing narratives of the community.

The objective becomes aligning voter empowerment into existing, accessible narratives of the community. —Rich Hollant

LW: Brian, can you explain how you engage with those social and human services organizations to encourage them to embrace voter engagement in the palette of services they offer to their constituents?

BM: Though a lot of our work provides the training and resources for “how to vote,” we also provide the compelling reasons for “why to vote.” The people that we engage with might be a front-line staffer at the nonprofit, the policy director, or program director. They need to make solid arguments to sell what we are proposing up their chain of leadership, to their board, and CEO. We do a lot of webinars, trainings, and provide written resources. We articulate why it’s central to their mission, and how voter engagement helps them do their work more effectively. We share resources showing how it strengthens the nonprofit, how it deepens trust in the communities they serve because the public will stop considering them just as a place to pick up food, for example, but as an active member of their community. It represents leverage for policy work by demonstrating that the folks they serve are registered because their organization registered them. It doesn’t take a lot of persuasion once we show that when the community is more engaged, political leaders are going to pay more attention. There’s research evidence that shows that people’s health outcomes are better and their sense of isolation is lower when they participate in voting and the broader civic society.

LW: A lot of people are very cynical about their ability to affect policy change. Take gerrymandering for example. What’s our potential to address this problem through design?

RH: I think a coordinated full-court press from a myriad of directions. Design articulates choice at a time when there are seemingly no choices or only binary choices. Design could open possibilities. We’re working right now with a group in Connecticut, called PoliticaCT. They are a group of politically accomplished women who’ve had first-hand experience running for public office, who have access to funding, and who are looking to increase the number of women running for public office in winnable districts. They don’t differentiate based on party affiliation—they care about a candidate’s position on a list of specific issues. They are demonstrating that opportunities for change are in the issue space, in shifting the demographics of our elected officials to look and think like the population they represent, in short wins in key districts, in leveraging experience, funding, and connections.

Design articulates choice at a time when there are seemingly no choices or only binary choices. —Rich Hollant

This organization would be at a loss without strategic coalition-led design thinking. Ultimately, the success of organizations like PoliticaCT will be measured in terms of intended shifts in public policy. Though I think design thinkers can be partners at the intersection where these changes occur. Our super powers are in orchestrating the intersection itself—managing the facilitation of multidisciplinary actions where we drive the consensus agreement of a community forward. I see that as a viable change theory for our design work on this project.

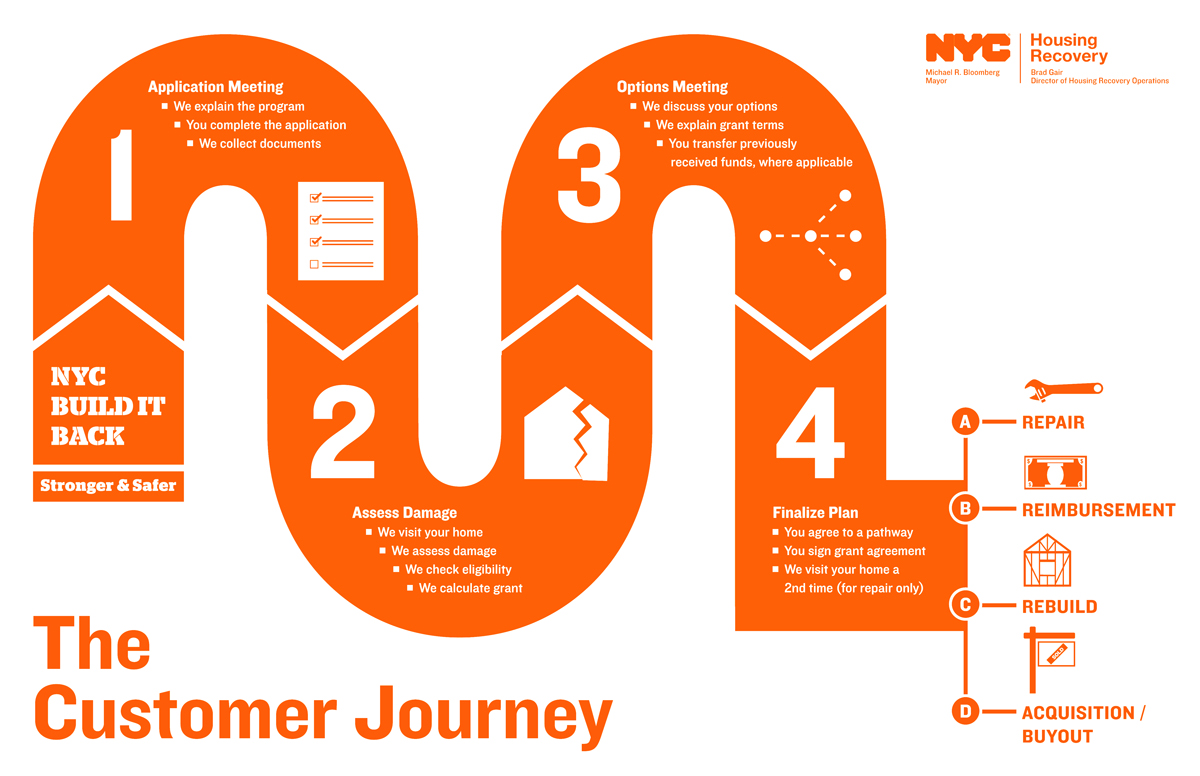

Branding campaign for NYC Build it Back, made in collaboration with Cloud Red and Office of Jeff. Image courtesy Nikki Chung and Dungjai Pungauthaikan, Principals at Once-Future Office, who was just selected by AIGANY to collaborate with Community Votes, as part of the Building Community Power project.

LW: What do you think, Brian? Gerrymandering, particularly, because many people ask about it.

BM: I don’t think there’s a thing you can do on the design front to affect gerrymandering. That’s a political question that just has to be fixed. The courts have to fix it. The policy work has to fix it. Can you use design to inspire the organizers to do that? Sure. Can design convey the message about the importance of addressing gerrymandering and organizing around gerrymandering and maybe building public support for nonpartisan redistricting? Sure, you can use design that way, but at the end of the day, the only thing that’s going to fix that is changing policies.

RH: Gerrymandering exists because it serves the system as it was designed. The point of civic engagement work is to build the critical mass that shifts the power dynamic to one that is more equitable—one that’s representative of the people. I think ultimately, policy will reflect the mandates that are empowered by people and that’s how we’ll fix the issues that are off-kilter in our democracy. I know it sounds hopeful, but I also think hope is a good first step. Design can help counteract a good deal of cynicism and connect people to a sense of their power. There’s a values framework buried under the dust, but it can be made visible. If we’re going to win these challenges, we need to tap into the core values that drive social impact work. Through design we have a better chance of tapping into the values, cultural stories, personal narratives, and other constructs that affect the outcomes.

Through design we have a better chance of tapping into the values, cultural stories, personal narratives, and other constructs that affect the outcomes. —Rich Hollant

LW: Rich, what opportunity does this project bring to design and designers?

RH: As a design association, AIGA’s members have a handle on assessing value through interpersonal relationships and ethos. Whether it’s monetary value or community value, we can leverage it for change, and I think that’s been an attribute of design all along—in particular, persuasion design, which seeks to understand why people are motivated to choose X or Y.

There’s another piece of design that I think is going to be critical to tap into for this partnership to be successful—system design. How do we first, decide on t the actions that we’re seeking to provoke, and then design more efficient structures to sequence and distribute the power necessary to achieve the desired outcome? How do we put the third eye on civic engagement so that conditions we thought of as barriers to participation no longer exist? That’s the other aspect of what design does well—it holds space for solutions not yet manifested.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Laetitia Wolff

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Recent Posts

Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsibleRelated Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews