Editor's Note: Excerpted from A History of the World (in Dingbats) © 2022 by David Byrne. Reproduced by permission of Phaidon. All rights reserved.

Dingbats?

Isn’t a dingbat a stupid person? Yes, that’s the common usage.

But that meaning may have derived from the word for a meaningless typographical element —nonsense symbols used by typesetters long ago both to give layout instructions to a printer (a person, not a machine) and to create visual breathing space in a type layout.

These meaningless glyphs eventually morphed into little drawings and icons that are often used to break up imposing and intimidating blocks of text. A flower pot, a bird, a cup and saucer, that kind of thing—they’re not usually meant to illustrate specific text content.

My drawings were conceived in that tradition, as a library of drawings to be used by the editors of the Reasons To Be Cheerful web magazine, but as soon as I began to draw I got carried away . . . they immediately assumed a life of their own. The editors didn’t seem to mind, and, once open, the faucet flowed.

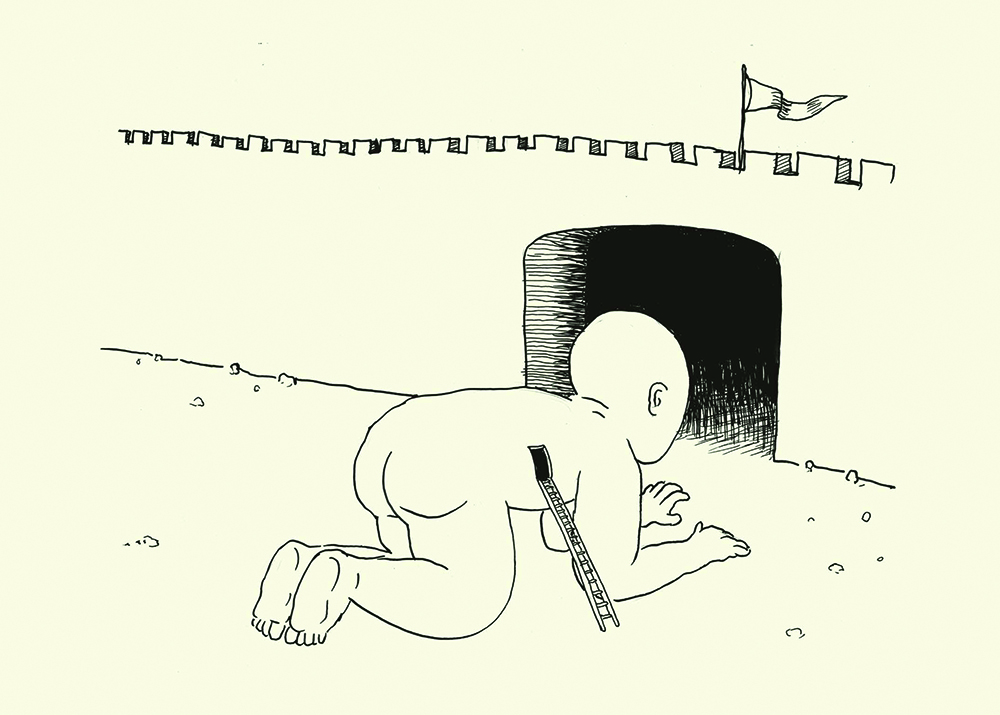

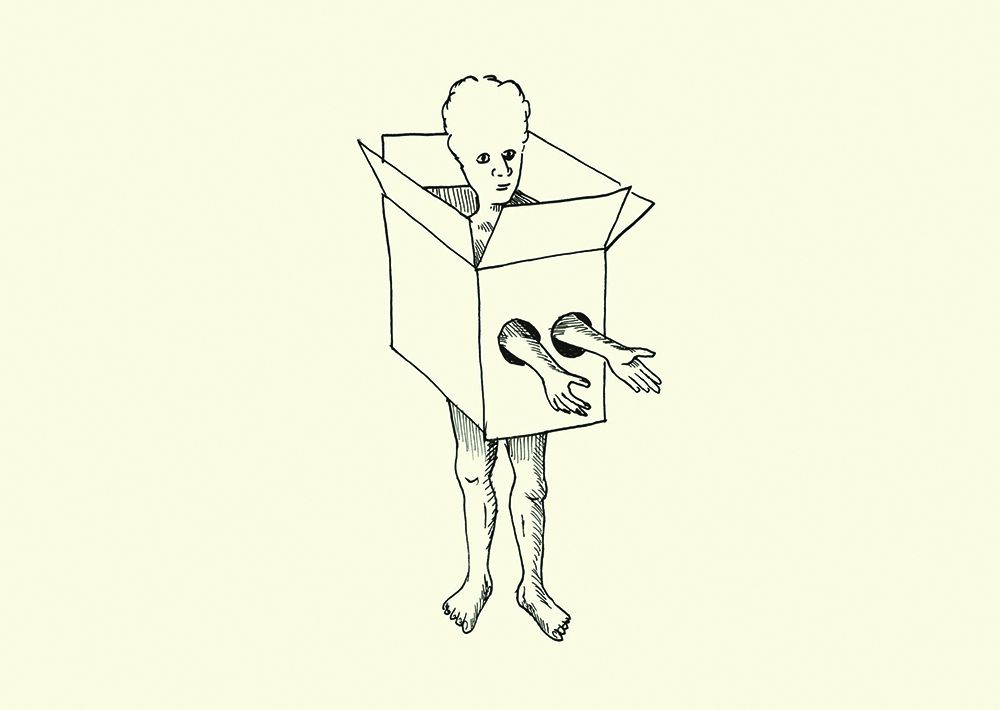

Trojan Baby. David Byrne / © 2022 Todo Mundo Ltd.

The drawings in this book were all made during the time of Covid . . . and quite often I can sense that mood comes through.

I can see there are thoughts about one’s body,

one’s mental state,

one’s priorities and values,

one’s household routines,

the world beyond one’s house or apartment.

Has my physical body, in effect, confined me? Did I forget to dump the kitchen compost?

Am I wondering if we’re all descending into apartment squalor?

Or is it just me?

Do I need to shower for a Zoom call?

Do I have to wear long pants?

What really matters to me?

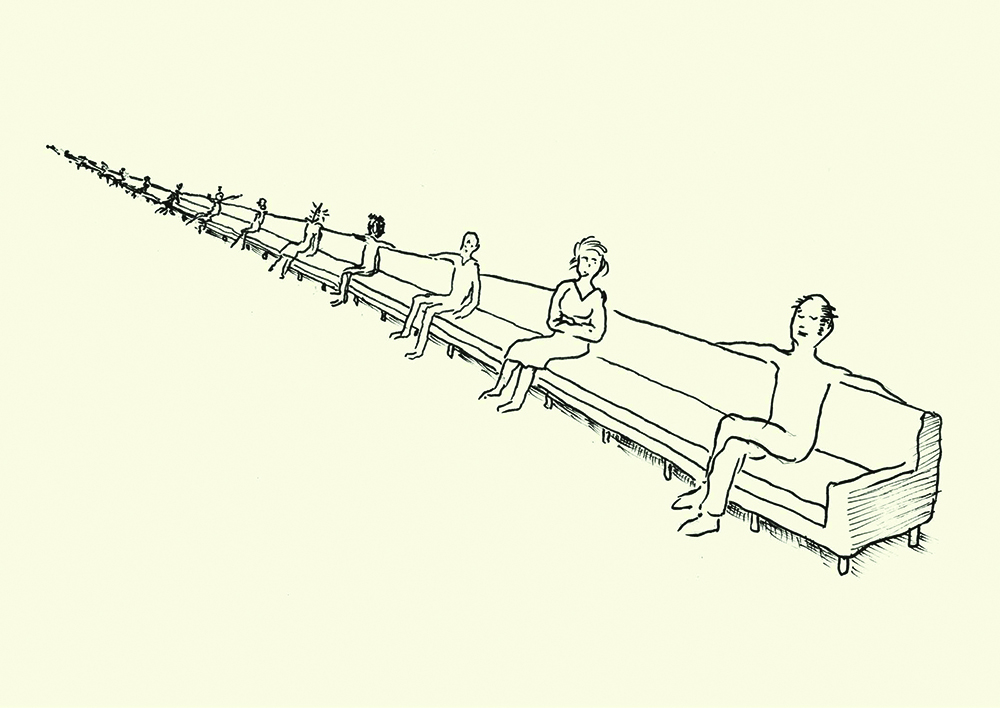

Have we all been going along in our lives

without stopping to question anything?

Aren’t other people what really matter to me?

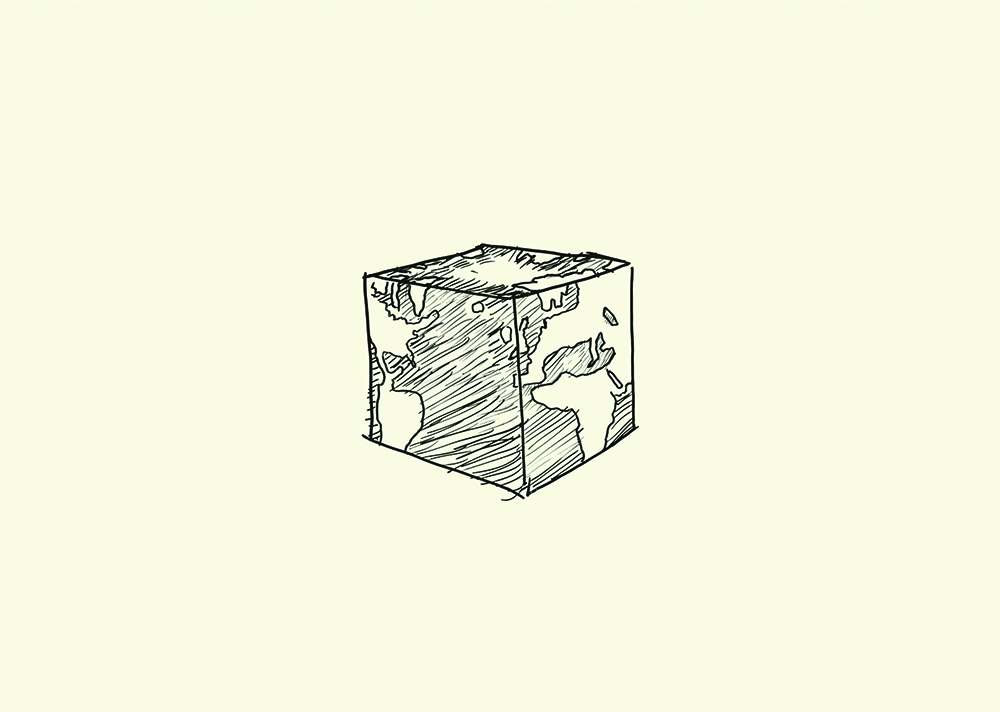

The Reasonable World. David Byrne / © 2022 Todo Mundo Ltd.

Although I didn’t realize it when I began, the drawings fell into recurring categories. These became the chapters, and in a way they accumulate, as our experiences did, and a kind of narrative emerges.

My own fears and desires—

which I assume are shared by so many others

who have gone through and survived

this surreal, tragic, revelatory, and unsettling experience—are not unique.

We who have survived have been transformed—in ways we are often unaware of. These changes in who we are and how we feel keep mutating and changing.

How we felt when this began is not how we felt a year later—

that seems pretty obvious.

These drawings, I realize, have become a record, a history, of those changes.

David Byrne / © 2022 Todo Mundo Ltd.

My hope is that others will recognize themselves in some of these images. I assume that, like songs, they’re not just about me.

Does everyone remember the days when touch transmission was a worry? (It turned out to be very unlikely.)

When every door handle or railing was a thing to be avoided?

It seems to me we can’t wait to move on—no surprise—but there is the risk of forgetting. The curtain was pulled back on “nor mal” and it became obvious that we actually didn’t want things to go back exactly as they were.

It is a moment to imagine how things can be better than that.

The drawings are not a direct commentary on specific societal issues laid bare —but maybe they begin to articulate how we feel. Joyous yet also frozen.

Fragmented yet unified.

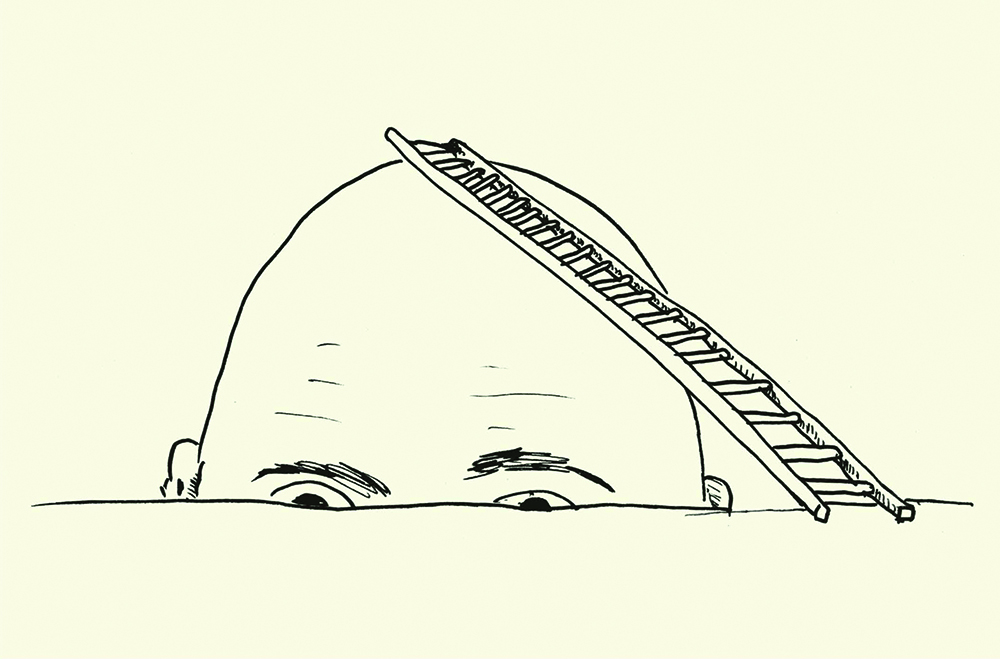

Box game. David Byrne / © 2022 Todo Mundo Ltd.

Those feelings will stay with us for a long time, when specifics are long forgotten.

They become part of who we are.

The titles of the drawings are, I believe, often integral to what they are. While calling an artwork “untitled” does generously open it up to wider inter pretation, it also shows a lack of commitment. Give your child a name!

I often look at one of these drawings, just before I title it, and I ask myself, “But what is it really about?” The titles are sometimes an attempt to answer that question, or at least they hint at a meaning beyond a simple literal interpretation.

It’s hard to put it into words, but if a friend chuckles while looking at some of these then I presume they understand that sometimes a drawing of cheese is not just a drawing of a fermented dairy product. Their reaction makes me smile because I sense they too realize it’s really about something else. It’s maybe something we’ve all been experiencing, and this is a way of sharing and recognizing that.

The history of the world is a story we tell ourselves.

Though the permanency of writing has slowed the process, these stories we tell ourselves about the world are not fixed. They are ever and continually revised and changed. History is not what happened, but it is what we agree happened—shaped by our biases and self-serving interests.

Stories are lessons we send to ourselves—some remain vibrant and relevant while others are only useful for a moment. They serve myriad purposes that are often beyond our ken, for better or worse, and sometimes both at the same time.

Propaganda and parables, delight and deception, mystery and manipulation.

Here is a story of a time made of pictures with names.

Infinite sofa. David Byrne / © 2022 Todo Mundo Ltd.